Welcome to the

Healy Project

Join us on Facebook

Send us an Email

CANCELED–Healy Block Historic District Walking Tour–November 8

Because of a family emergency, we regret that we have had to cancel this tour. Thanks for your interest. Watch the blog for other upcoming Healy Project events.

Great news for Healy’s most famous Queen Anne houses: On Monday evening, March 23rd, at a meeting held by Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis with residents of the Healy Block Historic District, the proposed sound wall was defeated by unanimous vote among those residents present. In addition, a new proposed design for the I-35W expansion was presented and approved. Monday’s win for the Block is an inspiration for the preservation community: an example of how historic district residents can triumph during a long and challenging political process.

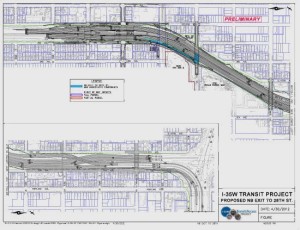

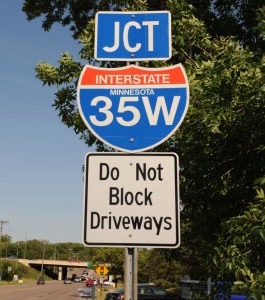

Plans for expanding and redesigning I-35W at the 31st Street exit have been in the works for a long time. Since the early 1990s, various plans have come and gone, representing serious threats to the Healy Block. In their current manifestation, expansion plans were introduced more than four years ago. Negotiation and discussion between the various government entities (federal, state, county and local) and the Block residents have been going on since then. (See post Threats to Healy Houses Renewed) Over a year ago Block representatives met with MNDOT commissioner Charles Zelle to work out some of the issues with the design. The new design and the nixing of the sound wall represent a significant win for livability of the residents on the Block and the future preservation of these historic houses.

David Piehl, who owns and lives in the J.B Hudson House on the Block, explains why eliminating the sound wall from the expansion plans is important: “A wall would be ugly, and the snow storage requirements for the freeway would mean the wall would be 10 feet closer to our homes than it currently is, in addition to being 20 feet high on top of the already-high embankment. Furthermore, the improvement in noise levels was projected to be around 5 decibels, which is not nearly significant enough for us to want to make the other sacrifices the wall would require.”

After the vote on the sound wall, discussion turned to the design of the off-ramp. Residents previously selected a design with a single-lane ramp, separated from Second Avenue by a median. However, the Federal Highway Administration vetoed it as “fatally flawed” due to lack of “storage.” That left another option which was very similar, but had a two-lane ramp.

At the meeting Block residents David Piehl, Ioannis Nompelis, and Pete Holly fought hard to keep the pavement and traffic as far from the historic houses as feasible. Residents recognize that Second Avenue on the 3000-3100 blocks serves three purposes–as a residential street, an off-ramp, and frontage road.

On Monday project organizers presented a modified design that has the ramp starting as single lane, then widening to two. They also widened the median separating Second Avenue from the ramp to 12 feet by taking a portion of the embankment. As Piehl reports, Block residents “are OK with this because it moves green space closer to our homes and the ramp further away. We wanted the median to be wide enough to be planted, so we can plant a visual screen between Second and the ramp, and we got that. A visual screen will also be re-planted on the embankment. The proposed median runs all the way to 31st Street. Second Avenue becomes a single lane with parking, but entirely separate from the ramp south of 31st. Even better, Second at 31st will be ‘right turn only’ due to adding 20 feet of boulevard space in front of the two homes on the 3000 block—which again moves traffic away from those homes, improving livability. The ‘right turn only’ lane reduces the appeal of 2nd Ave as a ‘frontage road’. The upshot is that Second Avenue will be a single lane residential street separated from the ramp by a 12-foot-wide, planted median.”

The miracle is that after four years of negotiating and fighting with the various entities involved in the I-35W expansion, residents of the Healy Block finally got nearly everything they asked for, short of moving the ramp. As Piehl says, “It is amazing to think that they started with bringing the freeway 30 feet closer, and a massive retaining wall–and we got them to a place where the plan is an improvement over what currently exists!”

This is a truly remarkable win for preservation in Minneapolis. Thanks go to a talented city planner, Jeni Hager, who diligently designed, re-designed, and re-designed again to ensure that the current proposal satisfied residents’ aesthetic and livability concerns as well as state and federal requirements. Many thanks also to supportive City Council members Elizabeth Glidden and Alondra Cano for their leadership. And finally, thanks and congratulations to David Piehl, Ioannis Nompelis, Pete Holly, John Cuningham (who worked for moving the ramp) and other Block residents who persevered and made it happen.

and did!

T.B.

“Merlin, if you don’t stop whining, I’m going to take Gwen’s sword and beat you to death with it,” said Arthur, evenly.

“It’s plastic.”

“So it will take me a long time. I’m still game.”

― FayJay, The Student Prince

|

| The Orth House later this year? |

|

| The Orth family on the porch of their house (2320 Colfax S.), 1890s. |

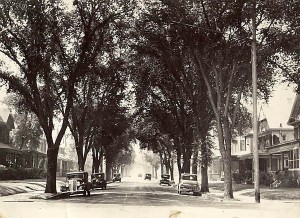

| 1936 photo of Second Ave S. from the 31st Steet intersection |

|

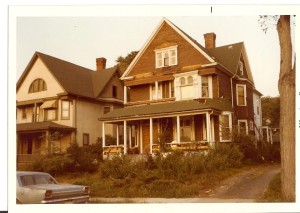

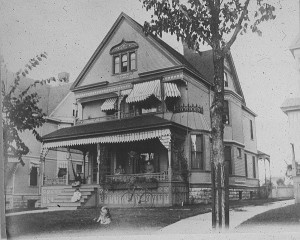

| The Hudson House in the days before people sitting on the porch didn’t see a freeway across the street. |

|

| Do not pave up to historic houses. |

|

| 3139 Second Ave. S, the second house Healy built (1886, $3,500) |

To receive notices about future tours and events, e-mail info@healyproject.org.

+ + + + + + + + + +

The Healy Project is celebrating its incorporation as a nonprofit with a tour of the Healy Block Historic District on Sunday, November 10th.

|

| The Rea House in the Healy Block Historic District (1890, $5,000) |

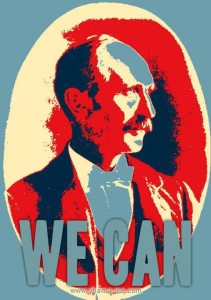

Motorists exiting northbound I-35W at Lake Street can’t help but notice the Queen Anne houses on Second Avenue, arguably the best known Victorian houses in Minneapolis. These fanciful survivors from a bygone era were designed and built by Theron Potter Healy, Minneapolis’s premier master builder. The entire west side of the Second Avenue block was wrecked in the 1960s during freeway construction. Over the years, fires, poor maintenance and redevelopment have taken others.

|

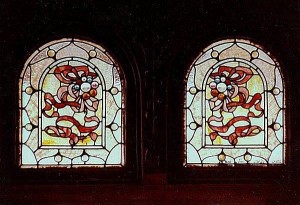

| Healy’s signature double-arch windows. |

Built between 1885 and 1898, these surviving houses, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, have endured thanks to the efforts of a small, but dedicated community. On Sunday, November 10th, the Healy Project is offering a different kind of home tour showcasing the community that has served as advocate for the houses of the Healy Block Historic District (3100 block of Second and Third Avenues).

The Healy Project’s inaugural tour aims to highlight and support the efforts of this community. Tourgoers will not only get the usual background into the houses’ architecture and history, but also background on the economic, cultural, and political forces affecting their past and future. Experts on real estate, community action, and historical research will talk about architectural preservation in the contemporary, living city.

|

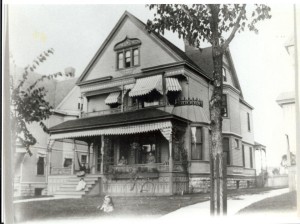

| 1890’s photo of the J.B. Hudson House (1890, $6,000) |

Preview of tour attractions: Background about the history of the Block and the struggles of homeowners in the neighborhood. The context of the Block in the Central neighborhood. A look at so-called “Undercover” Healy block (3200s Second Avenue), contrasting the houses there with the protected houses in the historic district. Healy homeowners’ success at saving other houses on adjoining blocks from demolition. An explanation of how a large Healy carriage house was lifted and replaced on its foundation. A look inside three early Healy-designed Queen Annes (built 1886, 1890 and 1891) on the Block. Information about a MnDOT plan that seriously threatens the entire Block. And more!

|

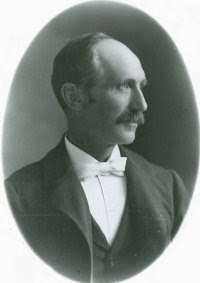

| Theron Potter Healy, King of the Queen Anne |

Registration is required to tour house interiors.

Tour-goers should assemble in front of 3139 Second Avenue South at 1 p.m. on the 10th. If you would like to see the interior of 3139, come earlier. Doors open at 12:15 p.m. A $10 donation to the Healy Project is suggested.

|

| Fishscale shingles on the gable end of 3139 Second Ave. |

If you have been in a fight to save an old house, you soon found out that these battles are political. Who has the power usually determines who wins–which is why so many preservation battles are lost. Money is power, and the forces of money are heavily weighted on the side of new development. Economic development is the name of the game, and if this means wrecking and rebuilding whole cities to keep the engine of late capitalism chugging, that’s what must be done (so they allege).

In Thomas Pynchon’s novel about New York before and after the 9-11 attacks, two characters are at the Pireus Diner, a funky old survivor of yupdating:

“I can’t believe this place is still here.”

“Come on, this joint is eternal.”

“What planet are you from again? Between the scumbag landlords and the scumbag developers, nothing in this city will ever stand at the same address for even five years, name me a building you love, someday soon it’ll either be a stack of high-end chain stores or condos for yups with more money than brains. Any open space you think will breathe and survive in perpetuity? Sorry, but you can kiss its ass goodbye.”

—Bleeding Edge (2013), p. 117.

That’s the observation of New Yorkers, but the scene could take place in any city in the world.

If old, cherished buildings are to be saved, preservationists need to have a clear idea of what they want to do and why. Who are these “preservationists”? Many disparate voices speak up for old buildings, and their reasons for doing so are as diverse as the groups they belong to. On one end of the spectrum is the Establishment. These are the people who come to mind most often when the word “preservation” is mentioned, the group(s) with both money and influence in government.

Chief among these is the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which, according to their website, is “a privately funded nonprofit organization [that] works to save America’s historic places. We are the cause that inspires Americans to save the places where history happened. . . . As the leading voice for preservation, we are the cause for people saving places.” The Trust and state-based organizations like the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota do great work–for example, funding studies on preservation-related issues (building green, encouraging tax credits), serving as liaisons with government entities, advocating for endangered buildings, running house museums.

|

| A Trust ad encouraging people to join in the cause of protecting historic tax credits. |

Many of their members are Players, or those connected with Players, people in government and the private sector who have influence over the outcomes of preservation battles. Some Players are elitists, those who are primarily interested in important monuments, like the homes of Victorian industrialists and elegant old apartment buildings. If they have enough money and political influence, they can have dazzling against-the-odds successes. Take, for example, the fight to save Grand Central Terminal (Reed and Stem, Warren and Wetmore,1903) in New York from being redeveloped with an enormous tower built over it. The battle, led by prominent New Yorkers like Jacqueline Kennedy, wound up being decided by the Supreme Court in 1978–the first case to be heard by that body on a preservation issue. Grand Central stands today because of the prestige and influence of its defenders against big money/big developers.

|

| The ceiling in Grand Central Terminal concourse, looking up from the main floor. |

At the other end of the preservation spectrum are the Grassroots preservationists. These are the small groups and individuals who, for reasons of aesthetics, sentimentality, or practicality, want to preserve old houses and their urban neighborhoods. They love the houses not because some big name architect designed them, or someone important lived in them, or something important took place there, but for other, perhaps more obscure reasons. Maybe they like the way an old house looks (or might look). Maybe they appreciate the craftsmanship and quality of materials in the old building. Maybe they simply can’t afford to buy a house of similar size and quality in a more upscale neighborhood. Or maybe it’s a combination of all of these. Whatever the reason, these preservationists of modest means band together when one of their own is threatened.

What distinguishes many of these Grassroots preservationists is that they are standing in the front lines of the battles with irresponsible landlords and predatory developers. They are the ones who are often at odds with city planning departments and the developers they are in cahoots with. Livability matters to them. If the once-beautiful old house next to theirs is rented to party-all-night cokeheads or hookers, or if two houses across the street are slated to be torn down and replaced by a soulless, fake-green apartment building, they are the ones who take action. Their cries for help may or may not be heard by the Establishment–usually not. Instead, they function as voices crying in the urban wilderness, banding together with like-minded homeowners, business owners, and tenants to save the old neighborhood from the bulldozers.

Grassrooters don’t have the money to fund a complete or even partial rehab or restoration of a house as soon as they buy it. Instead, they chip away at the rehab, doing some of the work themselves, bit by bit, as finances allow. I know because I am one of these preservationists. When we bought a ramshackle 1885 Queen Anne in 1976, it was in very sorry condition. All the woodwork had been painted, the exterior had two layers of siding, and all ornamentation had been removed. Alarmingly, some fool had removed part of a load-bearing wall to install a cold-air return, and the middle of the house was settling cellarwards. It took a lot of hard work and not a small amount of change over a 33-year period to whip the house back into shape. Over those decades my family endured frozen pipes, drafts, broken stair treads, carpenter ants, and dozens of other ills that old houses are heir too–including a haunting by a former owner. On one occasion, carrying a heavy can filled with old lathe and plaster, I fell through the floorboards of the summer kitchen. It was like living in the Money Pit, but without the money.

Whatever kind of preservationist you may be, If you care about Healy houses, or any other old house, the most effective way to preserve them is to join together. The best way to fight City Hall (or MnDOT or yupscalers) is to define your goal, band together, and spread the word.

–T.B.

Next: Examining what’s happening in and around the Healy Block Historic District in South Minneapolis. Despite their historic designation, the Block and other houses on nearby blocks are facing threats ranging from arsonists to a MnDOT scheme to widen Interstate 35W–which already took the west side of Second Avenue in the 1960s. Their historic designation itself is threatened by City approval of a variance allowing the “opening up” of the interior of the Bennett-McBride House, the only remaining Healy house with an intact original interior.