Welcome to the

Healy Project

Join us on Facebook

Send us an Email

Hypocrisy at City Hall: Planning Department Scorns Sustainable Development

It’s a common misconception that preservationists are sentimentalists out of touch with contemporary city planning practices and theory. Critics allege that preservationists block progress by fighting to save old buildings that stand where the City wants to erect new, higher-density construction.

|

| Copyright, National Trust for Historic Preservation |

The contrary is closer to the truth: current City support for sustainability in Minneapolis is long on theory but short on practice. The City website brags that “Minneapolis prides itself in being a leader in developing efficient, sustainable practices and facilities”. But when push comes to shove, new development almost always trumps sustainable development. Witness, for example, the current battles over redeveloping Dinkytown (http://www.startribune.com/local/minneapolis/187822971.html) and over the Lander proposal to wreck the Healy-built Orth House at 2320 Colfax Avenue South and put up a four-story apartment building.

|

| The six-story hotel proposed for Dinkytown. |

When these preservation battles went before the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission, City Planning’s official view was that the Orth House and the Dinkytown buildings are not historic and should go down. The HPC thought otherwise. Clearly, the City of Minneapolis pays lip service to sustainability, but favors new development.

Sustainable development is predicated on conserving resources by rehabbing or reusing existing buildings, rather than wrecking them and putting up new structures. According to the website of the World Bank, “sustainable development recognizes that growth must be both inclusive and environmentally sound to reduce poverty and build shared prosperity for today’s population and to continue to meet the needs of future generations. It must be efficient with resources and carefully planned to deliver both immediate and long-term benefits for people, planet, and prosperity.”

The needs of the poor don’t seem to be much of a concern for Minneapolis City Planning, which prefers to support development for the affluent—hotels, condos, apartments. (More about this in another post.) So, what about the second, protecting the environment and conserving resources? That also doesn’t seem to be a high priority of the City, which seems hell-bent on rebuilding already-flourishing neighborhoods (Dinkytown, the Wedge) with new, high-density construction. To Minneapolis Planning, the 1,890 new housing units that are built or under construction along the Wedge’s Greenway apparently are not enough for the neighborhood. Now two more apartment buildings are being proposed in the Wedge north of 24th Street, Lander’s 44-unit building on Colfax and Don Gerberding’s five/six-story complex on Lyndale Avenue at Franklin.

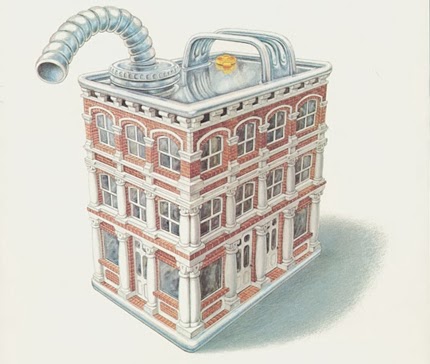

According to a study by the National Trust, even when a new, more efficient building replaces an existing building, it still takes as many as 80 years to overcome the environmental impact of the construction. Will the proposed new buildings even be around in 80 years? The Dinkytown development proposal slates a house and a commercial building for demolition. In the Wedge, two existing houses would be wrecked for the Lander building. The 6,400 square-foot Orth House alone is estimated by house mover John Jepsen to weigh 180 tons–limestone and virgin timber that would be removed to a landfill. (See the related post, “What’s the Greenest Building?” May 17, 2013)

|

| Business as usual is the route the City likes to go down–so much easier than planning and implementing sustainable development. |

Rehabbing the Orth House, adapting it to a new use, and/or incorporating it into new construction would be sustainable development. So far, the City has continued to promote the ill-conceived and wasteful Lander project, and just about any proposed new development that comes down the pike. Why? Re-fashioning or rehabbing old buildings takes planning, thought, design skills and knowledgeable local craftspeople, unlike erecting Tweedledum-Tweedledee new buildings. Moreover, new construction means more money for the developers, building trades, and ultimately, the City through higher density and increased tax base and valuation. Why fool around trying to save some old, rundown house when new construction will better serve your interests right now?

|

| Same old, same old in Minneapolis Planning: wreck the old, build new. |

It remains to be seen if wrecking permits will eventually be issued for the buildings now designated as “historic resources.” If so, the City will not be putting its money where its mouth is, but into the hands of developers of new construction.

|

| Reuse. Reinvest. Retrofit. Respect. |

Razing historic buildings results in a triple hit on scarce resources. First, we are throwing away thousands of dollars of embodied energy. Second, we are replacing it with materials vastly more consumptive of energy. What are most historic houses built from? Brick, plaster, concrete and timber. What are among the least energy consumptive of materials? Brick, plaster, concrete and timber. What are major components of new buildings? Plastic, steel, vinyl and aluminum. What are among the most energy consumptive of materials? Plastic, steel, vinyl and aluminum. Third, recurring embodied energy savings increase dramatically as a building life stretches over fifty years. You’re a fool or a fraud if you say you are an environmentally conscious builder and yet are throwing away historic buildings, and their components.

–Donovan Rypkema “Sustainability, Smart Growth, and Historic Preservation”

Preservationists are not, as critics claim, against development, but against stupid, shortsighted, development that is not sustainable. If the City wants to live up to its stated ideals, it needs to start encouraging and promoting rehab and reuse of existing buildings, especially historic buildings, for the benefit of current and future Minneapolis residents.

|

| The embodied energy of buildings (courtesy National Trust for Historic Preservation) |

Preservation is sustainability. Do the smart thing, Minneapolis: Shun the old planning orthodoxy that promotes outdated 1960’s types of developments and get on board with saving the city’s existing buildings.

Next: The economics of sustainable development

If you have been in a fight to save an old house, you soon found out that these battles are political. Who has the power usually determines who wins–which is why so many preservation battles are lost. Money is power, and the forces of money are heavily weighted on the side of new development. Economic development is the name of the game, and if this means wrecking and rebuilding whole cities to keep the engine of late capitalism chugging, that’s what must be done (so they allege).

In Thomas Pynchon’s novel about New York before and after the 9-11 attacks, two characters are at the Pireus Diner, a funky old survivor of yupdating:

“I can’t believe this place is still here.”

“Come on, this joint is eternal.”

“What planet are you from again? Between the scumbag landlords and the scumbag developers, nothing in this city will ever stand at the same address for even five years, name me a building you love, someday soon it’ll either be a stack of high-end chain stores or condos for yups with more money than brains. Any open space you think will breathe and survive in perpetuity? Sorry, but you can kiss its ass goodbye.”

—Bleeding Edge (2013), p. 117.

That’s the observation of New Yorkers, but the scene could take place in any city in the world.

If old, cherished buildings are to be saved, preservationists need to have a clear idea of what they want to do and why. Who are these “preservationists”? Many disparate voices speak up for old buildings, and their reasons for doing so are as diverse as the groups they belong to. On one end of the spectrum is the Establishment. These are the people who come to mind most often when the word “preservation” is mentioned, the group(s) with both money and influence in government.

Chief among these is the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which, according to their website, is “a privately funded nonprofit organization [that] works to save America’s historic places. We are the cause that inspires Americans to save the places where history happened. . . . As the leading voice for preservation, we are the cause for people saving places.” The Trust and state-based organizations like the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota do great work–for example, funding studies on preservation-related issues (building green, encouraging tax credits), serving as liaisons with government entities, advocating for endangered buildings, running house museums.

|

| A Trust ad encouraging people to join in the cause of protecting historic tax credits. |

Many of their members are Players, or those connected with Players, people in government and the private sector who have influence over the outcomes of preservation battles. Some Players are elitists, those who are primarily interested in important monuments, like the homes of Victorian industrialists and elegant old apartment buildings. If they have enough money and political influence, they can have dazzling against-the-odds successes. Take, for example, the fight to save Grand Central Terminal (Reed and Stem, Warren and Wetmore,1903) in New York from being redeveloped with an enormous tower built over it. The battle, led by prominent New Yorkers like Jacqueline Kennedy, wound up being decided by the Supreme Court in 1978–the first case to be heard by that body on a preservation issue. Grand Central stands today because of the prestige and influence of its defenders against big money/big developers.

|

| The ceiling in Grand Central Terminal concourse, looking up from the main floor. |

At the other end of the preservation spectrum are the Grassroots preservationists. These are the small groups and individuals who, for reasons of aesthetics, sentimentality, or practicality, want to preserve old houses and their urban neighborhoods. They love the houses not because some big name architect designed them, or someone important lived in them, or something important took place there, but for other, perhaps more obscure reasons. Maybe they like the way an old house looks (or might look). Maybe they appreciate the craftsmanship and quality of materials in the old building. Maybe they simply can’t afford to buy a house of similar size and quality in a more upscale neighborhood. Or maybe it’s a combination of all of these. Whatever the reason, these preservationists of modest means band together when one of their own is threatened.

What distinguishes many of these Grassroots preservationists is that they are standing in the front lines of the battles with irresponsible landlords and predatory developers. They are the ones who are often at odds with city planning departments and the developers they are in cahoots with. Livability matters to them. If the once-beautiful old house next to theirs is rented to party-all-night cokeheads or hookers, or if two houses across the street are slated to be torn down and replaced by a soulless, fake-green apartment building, they are the ones who take action. Their cries for help may or may not be heard by the Establishment–usually not. Instead, they function as voices crying in the urban wilderness, banding together with like-minded homeowners, business owners, and tenants to save the old neighborhood from the bulldozers.

Grassrooters don’t have the money to fund a complete or even partial rehab or restoration of a house as soon as they buy it. Instead, they chip away at the rehab, doing some of the work themselves, bit by bit, as finances allow. I know because I am one of these preservationists. When we bought a ramshackle 1885 Queen Anne in 1976, it was in very sorry condition. All the woodwork had been painted, the exterior had two layers of siding, and all ornamentation had been removed. Alarmingly, some fool had removed part of a load-bearing wall to install a cold-air return, and the middle of the house was settling cellarwards. It took a lot of hard work and not a small amount of change over a 33-year period to whip the house back into shape. Over those decades my family endured frozen pipes, drafts, broken stair treads, carpenter ants, and dozens of other ills that old houses are heir too–including a haunting by a former owner. On one occasion, carrying a heavy can filled with old lathe and plaster, I fell through the floorboards of the summer kitchen. It was like living in the Money Pit, but without the money.

Whatever kind of preservationist you may be, If you care about Healy houses, or any other old house, the most effective way to preserve them is to join together. The best way to fight City Hall (or MnDOT or yupscalers) is to define your goal, band together, and spread the word.

–T.B.

Next: Examining what’s happening in and around the Healy Block Historic District in South Minneapolis. Despite their historic designation, the Block and other houses on nearby blocks are facing threats ranging from arsonists to a MnDOT scheme to widen Interstate 35W–which already took the west side of Second Avenue in the 1960s. Their historic designation itself is threatened by City approval of a variance allowing the “opening up” of the interior of the Bennett-McBride House, the only remaining Healy house with an intact original interior.

|

| The Orth House, 2320 Colfax Avenue South |

|

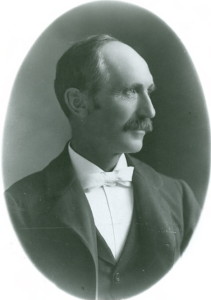

| Theron Potter Healy |

|

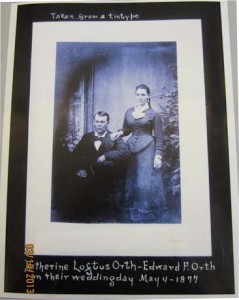

| Edward and Catherine Orth, first owners of 2320 |

|

| Anders Christensen being interviewed in front of 2320 by KARE-11 TV reporter Lindsey Seavert after the Z&P appeal hearing May 21st. |

In 1980 when then-Wedge-resident Anders Christensen examined the building permits for all the houses in Lowry Hill East, he discovered that a master builder named Theron Potter Healy had built 30 of them. Further research revealed that during his career (1886-1906), Healy had built over 120 houses and commercial buildings in Minneapolis.

In 1993 Healy’s most celebrated creations, the Queen Annes of the 3100 block of Second and Third Avenue South, received national historic designation as the Healy Block Historic District. In 1977 Healy’s Bennett-McBride House had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a superb example of the Queen Anne architectural style.

During the first Wedge Zoning and Planning Committee meeting on the Lander Group’s redevelopment plans for 24th and Colfax, architect Pete Keeley said he had contacted the City, and they had said the two houses slated for demolition had “no historical significance.” At the second meeting, another man supporting owner Michael Crow alleged that the Minnesota Historical Society, too, had said that the Healy house at 2320 was not historically important. I’m sure that both claims are true: Neither the City nor M.H.S. have anything on record about either house.

None of Healy’s Wedge houses have received historic designation, but that does not mean that they are not historic or architecturally significant. Many historic buildings have not received official historic designation (through the Historic Preservation Commission or the National Trust, for example), but that in itself does not speak to their importance.

Consider, for example, the Wedge’s own “Healy Block”, the 2400 block of Bryant Avenue South. Eight (probably nine) houses on this block are Healy’s: 2401, -05, -09,(-10),-20, -24, -28, -36, and -39, ranging in style from Queen Anne to Colonial Revival.

|

| 2439 Bryant, Colonial Revival, 1905 |

|

|||||||||||||

| 2409 Bryant, Queen Anne, 1895 |

On Bryant Avenue north of 24th Street (in the R-6 zone) are four other Healy houses; three of these are currently rooming houses. None of the houses on the 2400 block are rooming houses, although half of them were at one time. Former residents have told stories of tenants riding motorcycles up staircases, drunken brawls, drug deals, even murders taking place in these houses. Yet today, with the investments in time and money of their owner-occupants, they have become beautiful and valuable homes.

2320 Colfax, the Healy house slated for demolition, represents a pivotal point in Healy’s career. It is one of only two houses built by Healy in 1893. The other 1893 Healy house, 821 Douglas Avenue, was wrecked in 1981 by developer Paul Klodt. 1893 is a significant year in the history of architecture, the year of the Chicago World’s Fair. In this year the Queen Anne style began to fall out of fashion, replaced by the Colonial Revival style, made popular by the Fair’s “White City”. 2320 is Healy’s first Colonial Revival house, a significant part of his architectural legacy.

An old photo of 2320 reveals the original appearance of the house, with a large barn in back, and open field to the north:

|

| The Orth House, 2320 Colfax, as it appeared when new. |

|

| The house today. The porch has been enclosed, but the original roof line, profile, and fenestration remain. |

Obviously, some people don’t care diddlysquat about history or architecture, and this blog is not addressed to them. I have learned a very important lesson from my service on the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission and the Advocacy Committee of the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota: Governments and institutions are not concerned with saving buildings. Communities must define and speak out on what’s important to the community–and work to preserve it.

The 2004 LHENA Zoning Task Force clearly articulated what is important to Wedge residents, that is, ensuring the livability of the neighborhood by preserving the current mix of houses and multiple-unit buildings. Michael Lander has already redeveloped the southern part of the Wedge along the Greenway with high density apartment buildings and condominiums. This redevelopment makes sense in that it replaced a defunct industrial area. But the apex of the Wedge is a different story. Development supporters have made much of the idea of saving the neighborhood “core”, while keeping the “fringe” high density. Truth to say, the apex is such a small area that most of it can be considered “fringe” of the greater neighborhood, the current view from City Hall. The point is moot: R-6 allows high density throughout, so-called “core” included.

Last month a first in a series of meetings was convened by the City to look into the feasibility of establishing “conservation districts” in Minneapolis. Such districts would offer more protections than the zoning code, but fewer than those of historic districts, such as the Healy Block. A conservation district would certainly be a big step forward in saving the houses in the apex of the Wedge, but the idea is only at the beginning of a long planning process, with no guarantee it will be adopted.

|

| “360 Degrees of Wedge Healys”–Photo art by Richard Mueller |

In conclusion, I want to stress that if you want to save 2320 Colfax and preserve the other houses in the Wedge, don’t expect City Hall or an historical society to do it for you. Property rights are held sacrosanct in this country, and owners can wreck properties on the National Register if they so choose. Case in point–the developer in Arizona who wants to demolish a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Despite a firestorm of outrage and temporary stay of demolition from the City of Phoenix, the developer is still determined to take it down.

Former Zoning Task Force member Sue Bode said at the first LHENA hearing about the 2316-2320 plan, “Taking down a Healy house is like destroying one by Frank Lloyd Wright.” If you care about Healy’s legacy, if you care about the old houses of the Wedge, speak out.

|

|

| CAN PREVENT DEMOLITIONS! |

–T.B.