Welcome to the

Healy Project

Join us on Facebook

Send us an Email

Happy Earth Day, Zero-Credibility City of Minneapolis

On this day that celebrates Planet Earth, residents of our beautiful planet are urged to conserve dwindling resources by recycling everything from plastic bottles to buildings. The “Zero Waste” initiative of the City of Minneapolis similarly encourages citizens to conserve resources:

“Zero Heroes strive to have Zero Waste. They do this by working to first prevent waste, and then by recycling all they can of the waste that remains. To lower this amount of waste we need to take a step beyond recycling: waste prevention. Waste prevention is reducing the amount of waste and the toxicity of waste. Waste prevention saves natural resources, energy, and may even save you money.” City of Minneapolis Web Site

Minneapolis, the Zero Waste city, wants us to recycle and ride bikes–while the City sends hundreds of tons of historic house to the landfill.

However, while the City Solid Waste and Recycling Department is urging citizens to compost and recycle bottles and papers, the City Planning department has been facilitating the demolition of an historic house–which will send 180+ tons of materials to the landfill. This disconnect between saying and doing shows a gobsmacking hypocrisy: Citizens recycle while the City cancels out their efforts by a thousandfold in the demolition of one house.

“The facts are in – no matter how much green technology is employed, any new building represents a new impact on the environment.It makes no sense for us to recycle newspapers, bottles, and cans while we’re throwing away entire buildings and neighborhoods.It’s fiscally irresponsible and entirely unsustainable.”Jerri Hollan, FAIA

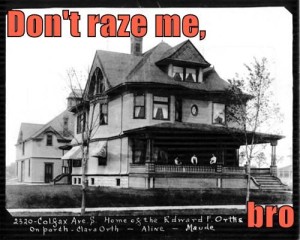

“Zero Waste” makes zero sense when the City shows blatant contempt for the most important piece of sustainability–recycling existing buildings. City Planning sent staffer John Smoley to the HPC twice to argue for its “save only the best buildings in the best neighborhoods” policy–and twice, after vigorous debate, the HPC affirmed that that the Orth House, 2320 Colfax Ave. S. is historic and should be placed under interim protection while a designation study is completed. But when the owner’s appeal to demolish was heard before the City Zoning and Planning, CM Lisa Bender, taking the unsupported testimony of the appellants as fact, declared that no viable alternatives existed to wrecking the house, and made a motion to overturn the HPC’s decision. The motion passed with no debate.

What the City plans for the Orth House and others in the Wedge and other not-good-enough neighborhoods.

“By 2030, we will have demolished and replaced nearly 1/3 of our current building stock, creating enough debris to fill 2,500 NFL stadiums. How much energy does this represent? [E]nough to power California (the 10th largest economy in the world) for 10 years. By contrast, if we rehabilitate just 10% of these buildings, we could power New York for over a year.”UrbDeZine SanFrancisco

The hypocrisy of the City regarding recycling would be laughable if it weren’t so appalling. Minneapolis needs to start practicing what it preaches. Citizens recycling cans and bottles is wasted effort if the government is not encouraging the recycling of buildings.

Don’t jive us, City of Minneapolis. Be a Zero Hero and affirm your alleged commitment to Zero Waste. Allow the historic Orth House to be recycled. The Greenest Building is the one standing.

In promoting their new projects, developers repeatedly trot out claims based on the tenets of New Urbanism: affordability, diversity, easy access, and sustainability.

“New Urbanism promotes the creation and restoration of diverse, walkable, compact, vibrant, mixed-use communities composed of the same components as conventional development, but assembled in a more integrated fashion, in the form of complete communities. These contain housing, work places, shops, entertainment, schools, parks, and civic facilities essential to the daily lives of the residents, all within easy walking distance of each other.”–NewUrbanism.org

Want to live in hip, starry-neon-skied Lime in the Wedge Greenway, where (as their sign proclaims) “tarts” are welcome? Prepare to shell out big bucks for a small space.

Let’s look at the claims of the Lander Group for its proposal at 2316-2320 Colfax Avenue South and see how they square with the aims noted above. Lander wants to wreck the Orth House at 2320 to clear the site for a 45-unit apartment building. The Lander website says that the 2320 project is “geared to more affordable budgets with the smaller sizing, and real transportation options.” To be cost-effective for the developer, the rents in new units need to be set at least at market rate. Currently, rents for 500-square-foot studios in new Wedge buildings start at $1200 per month. This is not “affordable” housing by any stretch of the imagination. Even if Lander/At Home do as stated keep the rent under $1,000 to start with (still above average for the area), there’s nothing to stop them from raising it afterward. This is exactly what happened at the joint Lander-Gerberding apartment project at 46th and 46th. They were initially advertised as market rate [1], but now are luxury [2]. If the developer is serious about affordability, let him sign a contract with the City for a fixed-rent range.

The fact is that the older rental units are the affordable ones. New apartment construction, to be cost effective for the developer, must have rents set higher than for existing structures. The result is what we now have in the Wedge Greenway: 1800+ units built or under construction that are inhabited largely by young, affluent white people. The aim of the marketing campaigns for these Greenway apartments is to attract young suburbanites to the city for a few years before they settle down in neighborhoods of mostly single-family homes: “Don’t get hitched until you enjoy your year at Lime”, “I don’t remember her name, but her apartment” (Elan). This kind of marketing and pricing does not produce a racially, socially or economically diverse community, but an enclave of privileged “urban tourists,” slumming in the Wedge for a few years. So much for developers adhering to the “diversity” and “affordable” parts of New Urbanist planning.

The Lander website touts “real transportation options” (as opposed to imagined options?) available to future tenants. “The building concept promotes ‘green’ living – close to and providing a variety of transportation options, services, recreation, and green space.” Lander’s “concept” has not produced these amenities, which are available to anyone living in the area. Bus lines run on Hennepin, Lyndale, and Franklin right now.The Wedge has always been a very walkable part of the city, close to lakes, parks, and shopping. Minneapolis is currently the most bike-friendly city in the country. Hour Cars are available now at Franklin and Dupont, a short walk away; bike racks can be built into any structure.

In addition, the developer and development supporters totally ignore New Urbanism’s mandate to conserve resources: to lift people out of poverty, to use energy wisely, and to build community. An important part of this mandate is to preserve the cultural resources and history of the community–an aspect developers conveniently forget, and in fact, as is obvious in the case of 2320 Colfax, scorn.

“Regional architectural styles, historic preservation and shared public space are also crucial.”—Charter for the New Urbanism

This is what the idealized sketch of the proposed Lander building looks like:

Architectural drawings are often out of context, a building surrounded by sky and trees (and sometimes a flock of birds). This building could go just about anywhere, a ho-hum block of flats that is hyped as “affordable” and “sustainable”–but isn’t. (See post on “Greenwashing Demolition). Imagine instead an adaptive reuse of the Orth House, designed to fit in with new residential construction on the site, a multiple-unit complex that would not require sending 250+ tons of building materials to the landfill.

“Cities grow, evolve and combining the new with the old in the same area will acknowledge the history of the place. Projects that pay homage to the existing fabric of a space, but also incorporate new architecture would be my ideal.”–Martina Ernst, Wo-Built Inc. – Innovative Design and Build, Toronto

The Lander proposal is designed with one primary goal: to maximize profits for the developer, with no regard for the neighbors or neighborhood. Let’s not forget that the Lander project did not win approval by the LHENA neighborhood board.

Lander, the property owner, and their for-hire expert contend that the Orth House does not have structural integrity. But don’t just take the word of people who will make hundreds of thousands of dollars from its demolition. John Jepsen of Jepsen Structural Services, a company specializing in structural shoring, lifting and straightening, has examined 2320 Colfax. Last year he testified before the City Council that the house is structurally sound, “built of old growth timber, straight and true.”

The owner and the broker who engineered the deal with Lander also contend that it would economically unfeasible to rehab the house. Again, are we to simply take the word of those who will reap substantial financial gain from its demolition? Those who have been inside the house, like myself, have found that many of the original features remain on the first floor and on the exterior.The upper floors were redone after a fire, but this provides interesting options for redesign.

A redevelopment that would include the Orth House would be the green, sustainable, affordable option, a reuse that would be sensitive to community concerns, city history, and fit in with existing buildings in the North Wedge.

Reuse. Reinvest. Retrofit. Respect.

–T.B.

|

| Despite losses and setbacks, Panamanian preservationists repeatedly took to the streets to protest demolitions for redevelopment. |

|

|

| The “emergency” demolition of the historic Fjelde House on Christmas Eve, 2009, is one example of the City’s stealth attacks on sites it wants to redevelop. |

|

| Another example is the middle-of-the-night demolition in 1975 of Calhoun Elementary School (built 1887) on what was to become the parking ramp for Calhoun Square. –T.B. |

I. The Sad History of Zoning in the Wedge (Lowry Hill East)

|

| Map of Lowry Hill East |

As followers of the Healy Facebook page know, in October, the Zoning and Planning Committee for the Lowry Hill East Neighborhood Association (LHENA) met to look at a proposal by the Lander Group to redevelop a site on the northwest corner of Colfax Avenue and 24th Street in the Wedge. The proposal, presented by Peter Keely of Collage Architects, called to wreck two extant houses, 2316 and 2320 Colfax, and erect a five-story, 48-unit apartment building. While emphasizing the “green” aspects of the proposed building, Keely also repeatedly stressed that it was considerably smaller than R-6 zoning allows.

After Keely’s presentation, the large group in attendance spoke of their concerns. Comments ranged from outrage at the size of the project to arguments in support of it from the man who owns the two houses, Michael Crow. The majority of the response was decidedly negative. At the end of the discussion, Steve Benson, chair of the 2004 LHENA Zoning Task Force. spoke eloquently of the need to secure the livability of the neighborhood by preserving the extant houses. Keely, after saying earlier that the proposal was the only “economically feasible” one for Lander, agreed to come back with another one at the November meeting.

What has all this to do with Healy? The Orth House at 2320, currently a 17-unit rooming house, was designed and built by Healy. According to Michael Crow, the original architectural features are gone, and it would be no loss to wreck it. The architect reported that City Planning agrees, saying that it has “no historical value.” Well, if the house really is as torn up as they contend, I wonder who’s responsible. Could it be Crow, who has run the place as a rooming house for the 21 years he’s owned it?

I will return to the historical and architectural importance of 2320 in another post, but now I’d like to focus on zoning issues and how they relate to preservation. I know, zoning is one of those topics that put people to sleep. But before you start dozing off, please try to keep awake long enough to learn the background of zoning in the Wedge.

In 1963 the City upzoned much of Minneapolis, including the Wedge, to high density R-6 zoning. These were the postwar days when much of old Minneapolis fell to the wrecking ball (the Metropolitan Building, for example). When the Wedge was upzoned, the houses started to come down by the scores, replaced by two-and-a-half story walkup apartment buildings. The City made the north-south streets into “paired commuter one-way corridors”, that is, racetracks for suburbanites to speed through the scary inner city.

In 1970, a group of Wedge residents banded together to form LHENA for the purpose of cleaning up and stabilizing the neighborhood. They picked up trash, they fought slumlords, they put unruly tenants on notice, they started “The Wedge” neighborhood newspaper. Their main goals, however, were to better control traffic flow and to downzone the Wedge to a lower density designation.

|

| Minneapolis’s first co-op market, the Wedge, was founded in 1974. |

Amazingly, LHENA partially succeeded in meeting these goals by getting rid of the north-south one-ways and by downzoning the inner core of the area south of 24th Street to R-2B. North of 24th Street, however, R-6 zoning remains in place for all of the existing houses. In 2004 LHENA’s Zoning Task Force submitted a detailed plan to the City, arguing why downzoning the Wedge apex is essential for retaining the unique character and livability of the neighborhood. The City (figuratively) threw the study into the wastebasket. Apparently the City is quite happy with R-6 in the apex and is looking forward to cramming into it as many units as possible.

On November 14th, Peter Keely returned to the LHENA Zoning and Planning Committee with a new plan for the 2316-20 redevelopment. The revised proposal, it turns out, requires no variances from the City to build. Big surprise, eh? The fact is that as long as R-6 zoning is in place, developers can build pretty much whatever they want, without the blessing of the community. Presenting this plan to the zoning committee is simply window-dressing for Lander. At the second meeting, the focus was on hearing and commenting on the proposal. Anders Christensen was allowed to speak briefly on the historical significance of the houses. A man who identified himself as a supporter of Michael Crow claimed that the Minnesota Historical Society says that 2320 has no historical importance (more on this in next post), and the committee’s attention returned to issues such as parking, the placement of garbage cans, the wonders of brownstone, etc. “Progress” marched on.

|

| Returning soon to the Wedge? |

The most alarming aspect of this seemingly benign proposal is that it signals a return to the Bad Olde Days of house demolition, with the attendant fallout of displaced tenants. After nearly four decades of stability, the residents of Lowry Hill East–and those at City Hall–must decide if they really want to see the apex of the Wedge turned into a nondescript Midwestern version of the Bronx, indistinguishable from other redeveloped urban areas–or if they want to retain the distinctive charm of the existing blend of houses and smaller apartment buildings.

The reality is that with R-6 zoning, developments like this cannot be stopped via the mechanism of City government. But that is not to say they can’t be stopped. Lowry Hill East’s nickname “The Wedge” came about not only to reflect the shape of the neighborhood, but the direction of its political thrust.

If and when these two houses fall, others will inexorably come down, too. It would be the end of the Wedge as we know it. Preservationists, those who love the Wedge and its houses, it’s time to stand up and be counted.

–T.B.

Next: The architectural and historical importance of Healy houses in the Wedge.