Welcome to the

Healy Project

Join us on Facebook

Send us an Email

Hypocrisy at City Hall: Planning Department Scorns Sustainable Development

It’s a common misconception that preservationists are sentimentalists out of touch with contemporary city planning practices and theory. Critics allege that preservationists block progress by fighting to save old buildings that stand where the City wants to erect new, higher-density construction.

|

| Copyright, National Trust for Historic Preservation |

The contrary is closer to the truth: current City support for sustainability in Minneapolis is long on theory but short on practice. The City website brags that “Minneapolis prides itself in being a leader in developing efficient, sustainable practices and facilities”. But when push comes to shove, new development almost always trumps sustainable development. Witness, for example, the current battles over redeveloping Dinkytown (http://www.startribune.com/local/minneapolis/187822971.html) and over the Lander proposal to wreck the Healy-built Orth House at 2320 Colfax Avenue South and put up a four-story apartment building.

|

| The six-story hotel proposed for Dinkytown. |

When these preservation battles went before the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission, City Planning’s official view was that the Orth House and the Dinkytown buildings are not historic and should go down. The HPC thought otherwise. Clearly, the City of Minneapolis pays lip service to sustainability, but favors new development.

Sustainable development is predicated on conserving resources by rehabbing or reusing existing buildings, rather than wrecking them and putting up new structures. According to the website of the World Bank, “sustainable development recognizes that growth must be both inclusive and environmentally sound to reduce poverty and build shared prosperity for today’s population and to continue to meet the needs of future generations. It must be efficient with resources and carefully planned to deliver both immediate and long-term benefits for people, planet, and prosperity.”

The needs of the poor don’t seem to be much of a concern for Minneapolis City Planning, which prefers to support development for the affluent—hotels, condos, apartments. (More about this in another post.) So, what about the second, protecting the environment and conserving resources? That also doesn’t seem to be a high priority of the City, which seems hell-bent on rebuilding already-flourishing neighborhoods (Dinkytown, the Wedge) with new, high-density construction. To Minneapolis Planning, the 1,890 new housing units that are built or under construction along the Wedge’s Greenway apparently are not enough for the neighborhood. Now two more apartment buildings are being proposed in the Wedge north of 24th Street, Lander’s 44-unit building on Colfax and Don Gerberding’s five/six-story complex on Lyndale Avenue at Franklin.

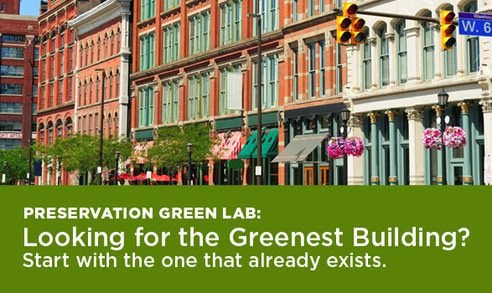

According to a study by the National Trust, even when a new, more efficient building replaces an existing building, it still takes as many as 80 years to overcome the environmental impact of the construction. Will the proposed new buildings even be around in 80 years? The Dinkytown development proposal slates a house and a commercial building for demolition. In the Wedge, two existing houses would be wrecked for the Lander building. The 6,400 square-foot Orth House alone is estimated by house mover John Jepsen to weigh 180 tons–limestone and virgin timber that would be removed to a landfill. (See the related post, “What’s the Greenest Building?” May 17, 2013)

|

| Business as usual is the route the City likes to go down–so much easier than planning and implementing sustainable development. |

Rehabbing the Orth House, adapting it to a new use, and/or incorporating it into new construction would be sustainable development. So far, the City has continued to promote the ill-conceived and wasteful Lander project, and just about any proposed new development that comes down the pike. Why? Re-fashioning or rehabbing old buildings takes planning, thought, design skills and knowledgeable local craftspeople, unlike erecting Tweedledum-Tweedledee new buildings. Moreover, new construction means more money for the developers, building trades, and ultimately, the City through higher density and increased tax base and valuation. Why fool around trying to save some old, rundown house when new construction will better serve your interests right now?

|

| Same old, same old in Minneapolis Planning: wreck the old, build new. |

It remains to be seen if wrecking permits will eventually be issued for the buildings now designated as “historic resources.” If so, the City will not be putting its money where its mouth is, but into the hands of developers of new construction.

|

| Reuse. Reinvest. Retrofit. Respect. |

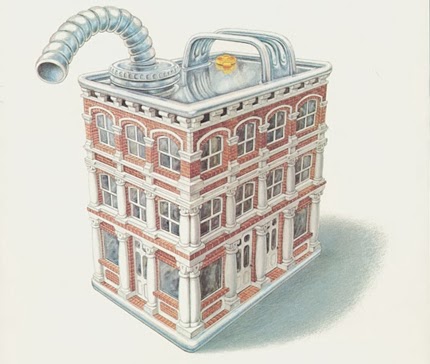

Razing historic buildings results in a triple hit on scarce resources. First, we are throwing away thousands of dollars of embodied energy. Second, we are replacing it with materials vastly more consumptive of energy. What are most historic houses built from? Brick, plaster, concrete and timber. What are among the least energy consumptive of materials? Brick, plaster, concrete and timber. What are major components of new buildings? Plastic, steel, vinyl and aluminum. What are among the most energy consumptive of materials? Plastic, steel, vinyl and aluminum. Third, recurring embodied energy savings increase dramatically as a building life stretches over fifty years. You’re a fool or a fraud if you say you are an environmentally conscious builder and yet are throwing away historic buildings, and their components.

–Donovan Rypkema “Sustainability, Smart Growth, and Historic Preservation”

Preservationists are not, as critics claim, against development, but against stupid, shortsighted, development that is not sustainable. If the City wants to live up to its stated ideals, it needs to start encouraging and promoting rehab and reuse of existing buildings, especially historic buildings, for the benefit of current and future Minneapolis residents.

|

| The embodied energy of buildings (courtesy National Trust for Historic Preservation) |

Preservation is sustainability. Do the smart thing, Minneapolis: Shun the old planning orthodoxy that promotes outdated 1960’s types of developments and get on board with saving the city’s existing buildings.

Next: The economics of sustainable development