Welcome to the

Healy Project

Join us on Facebook

Send us an Email

Perverting New Urbanism II: Greenwashing Demolition

Developers repeatedly trot out claims based on the tenets of New Urbanism: affordability, diversity, easy access, and sustainability. For example, as seen in the previous post, the Lander Group’s promotion of its 2320 Colfax project as “affordable” is not credible, given the rents required for units in new Wedge buildings. However, the Lander Group’s bogus claim of affordability is not the most egregious subversion of New Urbanist principles. A much more serious misrepresentation resides in the statement that this building will consist of “‘Eco-Flats – promoting ‘Green-Living’. . .close to and providing a variety of transportation options, services, recreation, and green space.”

What does this mean? Not that the building is green, but that the living in it will be green. How will this be green? By the developer putting in fewer parking spaces than will be needed for 45 units, providing an HourCar, a “variety of bike storage options”, and a bike-repair stand. First of all, the assumption that the majority of tenants won’t own cars is ridiculous. That’s an ideal of New Urbanist planning that is far from being realized. 80% of American adults own at least one car. If the project has the Wedge average of 1 1/2 tenants per unit, the complex could be short of parking by 34 spaces. Many workplaces are simply not accessible by public transportation, and many people who bike to work often suspend bike commuting during the winter. Second, the amenities available nearby (bus routes, bike paths, HourCar, parks, nearby shops and restaurants) are already there, and will be there, Lander project or not.

Using the prefix “Eco-” as a descriptor is a marketing ploy to suggest that this project will be good for the environment–which it most decidedly will not be. Wrecking the houses at 2320 and 2316 will cost the developer about $60k–to be added to construction costs–and would involve removing 250+ tons of building materials, excluding the foundations, to the landfill. Historic preservation is environmental preservation. According to the World Bank, “sustainable development recognizes that growth must be both inclusive and environmentally sound to reduce poverty and build shared prosperity for today’s population and to continue to meet the needs of future generations. It must be efficient with resources and carefully planned to deliver both immediate and long-term benefits for people, planet, and prosperity.”[1] The proposed Lander development at 2320 Colfax is decidedly inefficient in its use of resources. Ironically using the rhetoric of ‘green living,’ the developer seeks to destroy the Orth House and replace it with new construction–the least environmentally responsible option available.

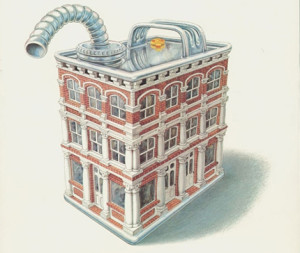

Article after article about conservation reiterates the point that “green building” is an oxymoron. You can’t have both. As Jerri Holan, a Fulbright scholar and member of the AIA, points out: “The facts are in – no matter how much green technology is employed, any new building represents a new impact on the environment.It makes no sense for us to recycle newspapers, bottles, and cans while we’re throwing away entire buildings and neighborhoods.It’s fiscally irresponsible and entirely unsustainable.” [2]

The Minneapolis Heritage Preservation and City Council have determined the Orth House to be an “historic resource.” Razing historic buildings results in a triple hit on scarce resources. First, we are throwing away thousands of dollars of embodied energy. The greenest thing we can do is to continue the life of a building whose resources have already been extracted from our planet. Using data from the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, we can calculate that the Orth House, at 6,400 square feet, embodies roughly 9.6 billion BTUS of energy, equal to 77,000 gallons of gasoline. If that building is torn down, all that embodied energy is wasted. What’s more, the demolition process itself consumes energy.[3]

The Lander website claims that their project would use “better construction techniques.” Hmm–better construction than what? Certainly not better than the house currently standing at 2320, which was built by T.P.Healy in 1893 of lumber from Minnesota’s virgin forests. The historic Orth House would be replaced with materials vastly more consumptive of energy. What is the Orth House built from? Timber, plaster, limestone, and bricks. These are the least energy consumptive of materials. The major components of new buildings, by contrast, are the most energy consumptive–plastic, steel, vinyl and aluminum.

An important part of New Urbanist strategy is the preservation of existing buildings and historic architecture. The reasons for this are twofold: historic preservation not only saves “places that matter” for future generations, but conserves rapidly dwindling natural resources and energy sources. The fact that the Lander project is a larger building than the Orth House does not offset the energy consumed in destroying the old one and building the new. Even if this building were LEEDS (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design)-certified[4] and built on an empty lot (which it is not), it would take many decades to offset the loss of resources. “By 2030, we will have demolished and replaced nearly 1/3 of our current building stock, creating enough debris to fill 2,500 NFL stadiums. How much energy does this represent? [E]nough to power California (the 10th largest economy in the world) for 10 years. By contrast, if we rehabilitate just 10% of these buildings, we could power New York for over a year.”[5]

New building can never be greener than existing structures, yet Minneapolis keeps saying it espouses sustainability while demolishing dozens of buildings annually. At the root of the problem is the functional life of new buildings. Contemporary buildings are considered to be disposable even as they go up. Take, for example, the Metrodome and the 1981 Walker Community Library building. These structures stood on sites cleared of older buildings for their construction. Only three decades years later, they both were demolished, sending thousands of tons of building materials to landfills. Meanwhile, across the street from the third Walker library, the first 1911 Classical Revival library building still stands, adaptively reused as commercial space.

New Urbanism is a comprehensive philosophy of urban planning. But so far, Minneapolis has been dealing with demolition on a case-by-case basis. An owner wants to wreck an historic resource: staff representing City Planning say, sure, wreck away. . .There are better examples of Healy’s work. This process of finding better examples of this and that can go on until there is literally one Healy house left standing. Lander’s development could have a suitable place in Minneapolis, but not on the site of the Orth House. If 2320-2316 were vacant lots, the Lander project would have already been built. Minneapolis should not be curating a museum, but maintaining community character and identity.

Minneapolis must develop a policy dealing with demolitions that takes into account both historical and ecological resources. Marketing buzz words should not be a substitute for responsible urban stewardship.

“Our duty is to preserve what the past has had to say for itself, and to say for ourselves what shall be true for the future.”–John Ruskin

–T.B

C.A.C.

Answer: The one standing.

So says Carl Elephante, Director of Sustainable Design at Quinn Evans Architects. Last year, the National Trust for Historic Preservation released a study, “The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse,” with data that supports this contention. The report uses Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) to compare the relative impacts of building renovation and reuse versus new construction. The description of the study says that it “examines indicators within four environmental impact categories, including climate change, human health, ecosystem quality, and resource depletion.”

|

| copyright, National Trust for Historic Preservation |

According to the study, wrecking a building and replacing it with a new one comes with very high environmental and economic costs. Let’s look at what how these costs apply to the wrecking of the historic Orth House at 2320 Colfax Ave. S.in order to build the Lander Group’s new four-story apartment building:

First is the cost of destroying the existing structure. Wrecking the Orth House (and its neighbor at 2316) will cost the developer approximately $30,000 each. Add to this cost, the waste of the building materials of the house. The Orth House, a large 6,000+-square-foot house, is estimated to weigh 180 tons, not including the foundation (John Jepsen, Jepsen, Inc.). The Orth House was built in 1893 of lumber from Minnesota’s virgin forests. This irreplaceable resource will be hauled off to a landfill, never to be used again. The plaster, lath, windows, and mechanical systems will similarly be trashed. Yes, some of these features could be removed for salvage; however, the sad fact is that staircases, doors, and windows in a house of this size and vintage cannot easily be fitted into an existing structure. To reuse them, one would have to custom build a structure they could fit into. And what’s the point of that when they are already serving their purpose in the existing house?

|

| The Orth House today. |

Second is the cost in labor and materials to build the new structure. New construction consumes many resources. The developer’s claim about energy savings makes no sense because new construction consumes so much energy upfront in producing new materials. (U.S.Green Building Council) The proposed apartment building is not one that uses a variety of “green” features and technologies, but a run-of-the mill structure. Recycling bins and bicycle racks do not a green building make. In fact, according to the Trust’s study, when replacing an average existing building with a new, more efficient building, it still requires as many as 80 years to overcome the impact of the construction.

|

| The Orth House c. 1900 |

Recycling existing buildings is essential to creating sustainable cities.

Minneapolis, do the right thing: Support sustainability and save the historic Orth House from the landfill.

–T.B.