Welcome to the

Healy Project

Join us on Facebook

Send us an Email

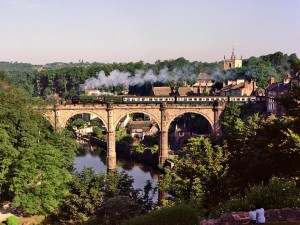

Henry Ingham’s Yorkshire

British Railways Riddles ‘Standard’ 9F 2-10-0 locomotive number 92220 EVENING STAR of York MPD crosses Knaresborough Viaduct. Wikimedia

I have always admired the work of Henry Ingham, a native of Knaresborough, Yorkshire, and one of Minneapolis’s “Big Three” master builders. But I never thought about visiting Knaresborough until I met a woman from Durham, England, on a 2014 trip to Norway. “Oh, you must visit Knaresborough,” she exclaimed. “It’s one of the most historic, quaint, and beautiful cities in North Yorkshire.” And so, last spring I planned a visit. (For a brief bio of Ingham, see http://healyproject.org/more-hauntings-houses-built-by-henry-ingham/).

In July I flew into Manchester, then took the train to Knaresborough, changing trains in Leeds. The train pulled into the charming old station, and I crossed the tracks and started up the very steep hill to my B&B. I had hoped to meet with local architectural historians, but my inquiries from the ‘States weren’t answered. However, as luck would have it, as I walked around town later that afternoon looking for Wellington Street, the 1861 and 1871 addresses of the Ingham family, I came upon some locals having a brew outside the pub. One of them kindly took me to the home of David Druett, a local historian who lives just around the corner from Wellington Street. From him I learned that only a few of the old houses on Wellington Street remain. It’s likely that the Inghams’ residences at #69 and #110 on that street were demolished for a post-WWII government housing project. Druett said that the three remaining old houses are workers’ houses from the 1840s, constructed cheaply (for that time), with relatively thin walls.

The front of David’s house on Brewerton Street with the postwar housing projects visible across Wellington Street.

It was a disappointment to find the two Ingham residences gone, along with most of old Wellington Street, so I turned my attention to what does remain in Knaresborough. What kind of influences on Ingham’s designs might I find?

Needless to say, the history of Knaresborough, an old market town, goes way back into antiquity. The first recorded mention of Knaresborough is in the Domesday Book, 1086. The Normans built a fortified castle on the bluff overlooking the River Nidd in the 1100s. The ruins of the 14th century castle, built by King Edward II, still remain. The castle was not ravaged by time, however, but by the Parliamentarians during the (English) Civil War. In 1648 demolition of the Royalists’ castle complex began. It would have been totally wrecked if the townspeople hadn’t petitioned to leave the King’s Tower remaining for use as a prison.

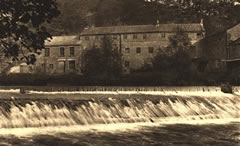

In the 19th and early 20th centuries Knaresborough’s economic base was the textile industry. The linen mill on the river began operating in 1791. “The structure might previously have been used as a paper mill, and adapted to new use shortly after November 1790 when a new water wheel was planned. Castle Mills was converted to flax spinning for linen in 1811 and Walton and Company leased it in 1847 for yarn spinning and power loom weaving, which took place in other buildings on the site. Linen production ceased in 1972 and Walton left the site in 1984.” [–from the designation of the Castle Mill building as a listed historic site].

Yorkshire was an industrial area throughout the Victorian period, known for its textile mills (linen, cotton, wool) large and small. In keeping with its new prosperity and importance, Yorkshire’s civic and institutional buildings were designed to impress. They’re massive and imposing, built of durable brick or stone.

While many pre-1900 cottages and houses were demolished during periods of “urban removal” through the centuries, many remain. Of course, I was primarily interested in the buildings from the mid- to late-nineteenth century. Knaresborough’s Victorian houses have primarily stone or stucco exteriors. I discovered that some of the remaining mid-century buildings are embellished with the Neo-Classical ornaments that Ingham loved.

The three houses remaining on Wellington Street built in the 1840s. Note the ornamental cornice on the one at right.

Here are some photos of typical Victorian buildings in Knaresborough:

The Primitive Methodist Chapel, built 1851, (now apartments) in the courtyard behind the Wellington Street houses.

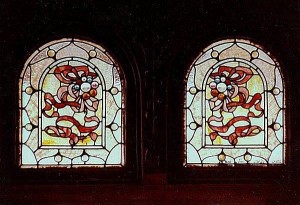

The Gracious Street Methodist Church Hall, with image of John Wesley. Wesley, the founder of Methodism, visited Knaresborough a number of times and left his mark on the town. The inghams were Methodists, as was the other Minneapolis master builder from West Yorkshire, Henry Parsons.

Playful contemporary trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) painted door and window on the side of an old building on Market Place.

This is just a guess, but young Henry Ingham must have seen that there were not many opportunities for making a career as a master carpenter or builder of wood frame houses in North Yorkshire. Sometime between 1871 and Thomas Ingham’s death in 1881, the family moved to the industrial city of Bradford, West Yorkshire. Armed with his certification as a master carpenter and joiner, in 1883 Henry Ingham, accompanied by his brother Alfred, lit off for the prairie boom town of Minneapolis. There in 1884 the Inghams built their first house at 3020 First Avenue South (wrecked in 1963 for freeway construction, as were so many of Healy’s houses).

Thomas Ingham family after his funeral, Bradford, Yorkshire, 1881. Henry standing at far left, back row.

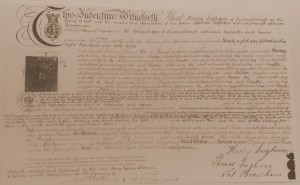

Henry Ingham’s papers of indenture as apprentice to Lot Brayshaw, carpenter and joiner of Knaresborough, 23 July 1868.

In 1890, Henry began designing and building houses on his own, and Alfred’s name disappears from the building permits. In his long career, 1884-1913, Henry built over 120 structures, including houses, apartment buildings, barns, and architect-designed residences. The interiors of his houses show exquisite craftsmanship in the millwork and cabinetry; the exteriors have a classical, understated grace. Yorkshire’s loss was Minnesota’s gain. In turn-of-the-century Minneapolis, master carpenter-builder Henry Ingham found his métier.

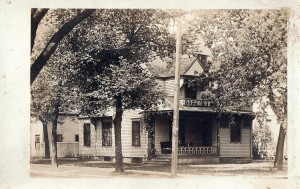

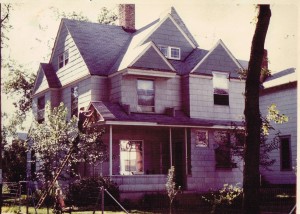

3146 Portland Ave. S. 1892, $6.000. The “Pink Ingham.” A flamboyant Ingham transitional Queen Anne, decked out for Halloween. (Photo by Madeline Douglass)

2432 Bryant Ave. S. 1899, $3,200. Ingham built this for Emma Goetzenberger, who apparently had excellent taste in builders. Healy and Purcell also designed and built houses for her in the Wedge.

+++++++++++++++++++

Many thanks to Kathy Kullberg and Ezra Gray for researching the Ingham family in Yorkshire. Thanks also to David Druett for giving me a glimpse into Victorian Knaresborough.

Ingham building research by Anders Christensen.

Photos without source noted are by Trilby Busch. Please credit if you reuse.

The Healy Project is planning a tour of Ingham houses in the not-too-distant future. Watch this blog for notices.

–T.B.

Because of a family emergency, we regret that we have had to cancel this tour. Thanks for your interest. Watch the blog for other upcoming Healy Project events.

28 August 2015

The fire is out and everyone is safe. Now what?

After the firefighters left (“You have a beautiful house, but your kitchen is a disaster”), we started cleaning up the water and dirt left on the first floor wooden floors. We went to Walgreens and picked up another mop and bucket to supplement the one we had at home. The kitchen has a tile floor and the water from the fire hose flowed through the floor directly into the basement. So, we had two inches of water in that area of the basement. Fortunately, that is where the laundry is located and there is a drain there and eventually the water went down the drain after soaking the bottom two inches of everything.

We mopped up the water and soot from the floors that lead from the kitchen to the front and back doors. We kept the front and back doors open to let out the smoke residue. And slept another half hour.

We called our insurance agent at about 8:30 am and heard from an adjuster within an hour. We lived in the house for two more days. Everyone said to not stay there and breathe the smoke residue. We finally agreed. We should have moved out right away. We stayed at a friend’s place for a couple of days while the insurance company set up a hotel downtown.

The insurance company sent us some names of fire mitigation contractors they have worked with in the past. We looked at their records, including with the Minnesota Dept. of Labor and Industry’s Residential Contractor licensing system and a neighbor who used one of the contractors. We selected a company that did an excellent job on another old house fire. They were able to accurately reconstruct that old house look we are looking for.

Meanwhile, we had to get all our clothing, bedding, and curtains cleaned. They all smelled of smoke. Ditto with all our electronics: TV, DVD, clock radios, computers, spare hard drives, etc. All three floors of the house filled with smoke due to the fire in one room. (More about these subjects later.)

An 1885 house will be open to tour on Saturday, April 25th, 1-2 p.m. The Twin Cities Vintage Homes Group is sponsoring the tour, with the proceeds to be donated to the Healy Project.

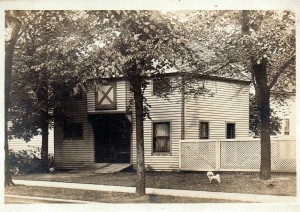

The barn in 1915. The hay mow level was cut off during the 1930s, when the structure was converted into a garage. The little dog, “Taxi”, was the Cartwright family pet.

Sign up for the tour on the Twin Cities Vintage Homes Group Meetup page. Space is limited, so don’t delay. To tour the interior of the house, you must preregister.

(Note: This is not a T.P.Healy design.)

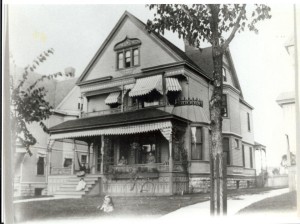

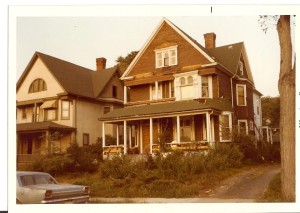

The rectilinear Queen Anne at 2648 Emerson Ave. S. in Minneapolis was designed and built by master builder Charles Johnson Buell. After owner Frank Cartwright died in 1942, the house fell on hard times. The Cartwrights had duplexed it during the Depression. Subsequent owners had painted all the woodwork and added two layers of siding, insulbrick and asbestos shakes.

The current owner acquired the house in 1976, and three years later the exterior restoration began with the removal of the siding.

Damaged clapboard was replaced, and the shingles on the gable ends repaired. Using the 1915 photo, master carpenter Doug Moore reproduced ornaments and trim. The house was painted in multiple historic colors.

The total restoration of the house took place incrementally, over 30 years. The woodwork in eight of the 12 original rooms has been stripped and refinished. In 1996 the summer kitchen was converted into a four-season room and 3/4 bath. Both of the chimneys and the front porch have been rebuilt. The interior restoration was officially declared complete in 2009 with the replication of the fretwork spandrel between the parlors–done by the same carpenter who reproduced the exterior trim in 1979.

The builder, Charles J. Buell, moved to Minneapolis from New York City in 1880. He served as principal of the Whittier School before becoming a builder. He built his first two houses in the Lowry Hill East neighborhood of Minneapolis in 1884; this house, built 1885, is his third. In 1888, he started building in St. Paul. From 1884-1919 Buell built 30 houses, 25 of which are still standing.

Buell Building List (compiled by Anders Christensen):

1884 402 W. Franklin (residence) Mpls.

2521 Aldrich Ave. S. $2,000

2525 Aldrich Ave. S. $2,000

1885 2648 Emerson Ave. S. $5,100

1887 2714 Girard Ave. S. $1,500 W

1888 2177 Commonwealth $5,000 SP

2173 Commonwealth $500

2210 (Langford N.) Hillside $2,400

930 Bayless $7,450 W

1889 2360 Bayless $5.000

2230-32 (Langford N.) Hillside $5,000

2214 (Langford N.) Hillside $2,400

25 Langford Park West $5,000

1890 2223 Knapp $2,450

1094-96 E. Bayless $6,000 W

1891 977 W. Bayless $2,500

2219 Knapp $3,000

1898 1717 Irving Ave. S. Mpls.

1901 1859 Dayton $3,500 SP

1902 1791 Dayton $2,000

1905 2308 Commonwealth $3,500

1906 1879 Dayton $4.250

1541 Ashland $4,500

1909 1549 Ashland $4.250

1550 Laurel $5,000

1910 1546 Laurel $4,000

1534 Laurel $4,500

1911 1514 Ashland $3,500

1913 1540 Ashland $3,500 W

1528 Laurel $5,000

1915 4748 Bryant $5,000 Mpls.

4744 Bryant

1919 2173 Commonwealth $3,200 SP

TB

On the evenings of October 23rd and 24th, guests gathered in a restored 1892 Queen Anne house in Lowry Hill East to hear folklorist Trilby Busch tell ghost stories. Owners Christina Langsdorf and Ezra Gray staged the house with creepy Halloween accoutrements and set out trays of “mummies”, “ghosts”, and candy as refreshments. The storytelling itself was lighted only by candles and a single lamp.

On the evenings of October 23rd and 24th, guests gathered in a restored 1892 Queen Anne house in Lowry Hill East to hear folklorist Trilby Busch tell ghost stories. Owners Christina Langsdorf and Ezra Gray staged the house with creepy Halloween accoutrements and set out trays of “mummies”, “ghosts”, and candy as refreshments. The storytelling itself was lighted only by candles and a single lamp.

Ezra tells guests about the house, built by master builder P.C. Richardson–who coincidentally was born on the same day and in the same year as T.P. Healy.

Trilby retold ghost stories she has collected about houses in Minneapolis, St. Paul, Duluth, and smaller towns in Minnesota. One of the stories was about a ghost who had haunted a house in the neighborhood. On Saturday night, when the storytelling ended, Christina announced that their eight-day clock in the front parlor (which had been wound up that afternoon) had stopped short of 8:30, as Trilby was telling this story. The clock had worked perfectly for years without stopping. Had the ghost dropped by to alert them that he is still around?

OMG! The photographer accidentally captured this image as he was shooting the event. Get out the EMF meter!

–Event photographs by Richard Mueller

–Decoration photographs by Christina Langsdorf.

|

| Healy as young man |

Anders Christensen “discovered” the houses of T.P. Healy through his 1979-81 survey of building permits of houses in the Wedge (Lowry Hill East ) neighborhood of Minneapolis. His initial research found 30 houses, 27 of which are still standing. He then turned to researching other neighborhoods of the city to learn more about Healy’s life and work.

Anders’ research was written up by Trilby Busch in a Twin Cities magazine article titled “Legacy of a Master Builder” (Nov. 1981). A photo from the article shows the builder’s descendants on the steps of the porch of the Bennett-McBride House, a Healy-designed Queen Anne listed on the National Register. Anders continues to work with one of these descendants, John Cuningham, a Minneapolis architect, in tracking down more information about Healy’s background.

|

| 3101 2nd Av. S., corner of the Healy block (1890). |

|

| Hardware, 1893 Healy Queen Anne |

The article outlines the story of Healy’s life, beginning with his birth in Round Hill, Nova Scota, in 1844. He later moved to Halifax, where he became a prosperous maritime shipper. However, disaster struck in August of 1883, when one of Healy’s ships was stranded in a gale off Cape Breton. Facing financial ruin, Healy and his family moved to the Dakota Territory, thence to Minneapolis, where he switched from building wooden ships to building houses. (For details, see article at http://www.sanfordberman.org/hist/healy/healyy.pdf)

Currently, Anders’ list of Minneapolis building permits taken out by Healy has 143 entries. He has compiled this list by searching through old building permits, then driving and walking around neighborhoods to confirm the information on these permits and to see which buildings are still standing. He has had the help of other architectural historians–Patty Baker, June Burd, Bob Glancy, David Erpestad, Paul Larson, and Dave Wood, and in recent years, Madeline Douglass, Brian Finstad, Sue Hunter-Weir, Ryan Knoke, Sean Ryan, Kathy Kullberg, Tammy Lindberg, Constance Vork, and Montana Scheff. It is his hope that by posting the information he’s found so far, other researchers will continue to help him build on this work.

|

| Fireplace in 1895 Healy Queen Anne. |

The posts for this blog are derived from Anders’ building list, beginning with Healy’s first house (1886) and continuing through those designed by Healy, and later architects, ending with his death in 1906. Through these posts, we hope to document the progress of Healy’s career from the designs his fabulous 1880’s and ’90’s Queen Annes, through the post-1893 Colonial/Neo-Classical Revival houses, to the large architect-designed houses of his later years.

–Trilby Busch